As the current Lord Justice Clerk, Lady Dorrian holds the second most senior judicial post in Scotland. This appointment made history in 2016 as no woman had ever served at this level in the Scottish legal system before. Leeona Dorrian’s status as a trailblazer began decades prior when she became the first woman to serve as Advocate Despute in the Faculty of Advocates.

Hilary Heilbron QC is an English barrister at Brick Court Chambers, with extensive experience in international arbitration and commercial litigation. She is also the daughter of Dame Rose Heilbron QC.

Yasmin Sheikh is a former personal injury lawyer and the founder of Diverse Matters, a consultancy that trains organisations on how to confidently approach disability and effectively tap into diverse talent. The organisation does this through training, coaching, mentoring, talks and webinars. Yasmin is also a speaker, thought leader and Vice Chair of the Lawyers with Disabilities Division at the Law Society.

Funke Abimbola MBE is a solicitor who has consistently used her voice to champion equality and diversity in the legal profession. She is the former UK General Counsel of Roche, the world’s largest biotech company. In June 2017, Funke was awarded an MBE for services to diversity in the legal profession and to young people.

Laura is the President of the Mental Health Tribunal for Scotland and Procurator to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. She is an expert in civil litigation, with a particular focus on delict and public law. This has seen her serve as Senior Counsel to the Penrose Inquiry and as the first female Scottish Law Commissioner.

Dame Alison Saunders was the second ever female Director of Public Prosecutions and the first lawyer from within the CPS to be appointed to the role. Alison is now a Dispute Resolution Partner at Linklaters.

Carolyn McCombe is the former Chief Executive of 4 Pump Court, a role which was newly created when she filled its shoes. Carolyn began her career as a litigation solicitor, rising to partner by age 30, before taking the unusual step of joining a barrister’s chambers as a junior clerk. Since then, she has risen through the profession to become a leader in practice management.

An exclusive interview with Dame Fiona Woolf for First 100 Years. Fiona is a British corporate lawyer, and served as Lord Mayor of London 2013-2014, the second woman in 800 years. Born in Edinburgh, Fiona qualified as a solicitor in 1973. She worked at CMS and became the firm’s first female partner in 1981.

Dame Vera Baird QC is currently the Victims’ Commissioner for England & Wales, responsible for promoting the interests of victims and witnesses of crime. She previously served as a Labour MP, the Solicitor General for England & Wales and a Police and Crime Commissioner. This was after practising as a criminal barrister for many years.

At the age of 31, Briony Clarke became one of the youngest ever female judges in the UK upon her appointment as a Deputy District Judge in 2017. Alongside her part-time appointment, she practised as a criminal law solicitor. Briony is now a full time District Judge and sits in Birmingham.

Anna Midgley was the youngest woman appointed a judge when she was appointed as a Crown Court Recorder in 2016 aged 33. She is also a criminal barrister, specialising in a broad spectrum of offences.

My great-grandmother’s life was a series of firsts for the female legal profession. Beginning her career as the first woman called to the Bar by Gray’s Inn, being the first woman to appear at the Manchester Bar and the first to be presented with a ‘red bag’, by age 28, Edith had already made history three times. However, her greatest legal achievement was undoubtedly being the first woman to preside over the County Court as a Deputy Judge.

Edith’s legacy as a trailblazer is seen not only in the legal profession as a whole but also in my own family. One of Edith’s daughters, Anne, (my grandmother), followed in her mother’s footsteps and was called to the Bar in 1951. Subsequently, one of Anne’s daughters, Helen, (my mother) pursued a career in law, qualifying as a solicitor. As a law student myself, and therefore, of the fourth generation of women to study law in my family, I have come to appreciate Edith’s story on a personal level.

We’ve got a woman on the Bench today.

Edith Hesling was born in Flixton, Manchester on the 22nd June 1899 to William Hesling, a wholesale merchant and Emma Edith Fairbairn. She was the eldest of four children and was raised in Heaton Moor, Stockport. After attending the Manchester High School for Girls, Edith was awarded a law degree from the Victoria University of Manchester (now the University of Manchester). A year later, on the 13th June 1923, Edith earned the distinction of being the first woman called to the Bar by Gray’s Inn. The historical significance of this moment is best captured by Edith’s admission slip from 1920 which reads ‘Received of Miss Edith Hesling the sum of Five Guineas on his admission to the Honourable Society.’

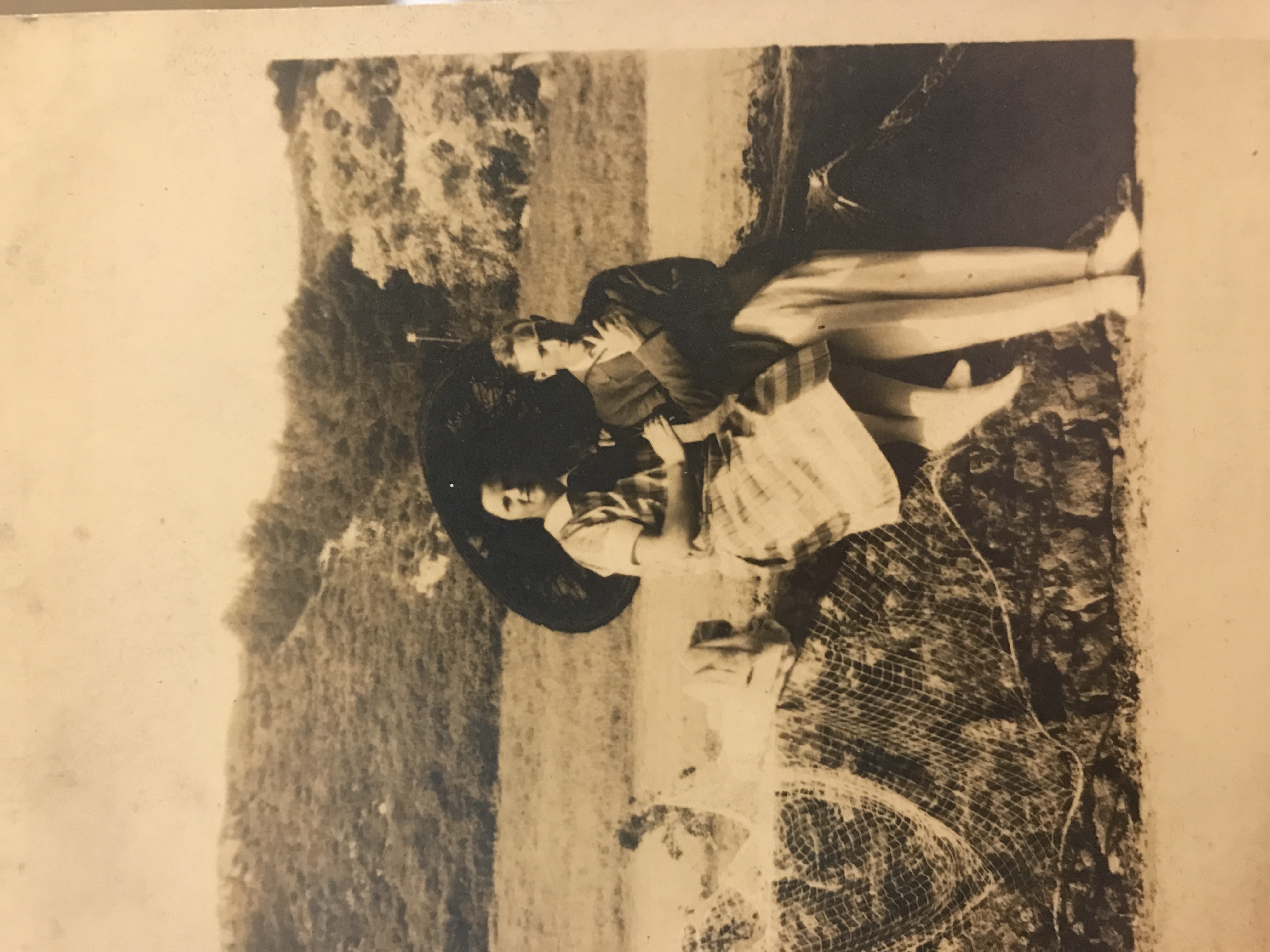

In 1927, Edith’s personal life changed significantly. On the 28th July, Edith married Frank Bradbury, with whom she had three children, twins Anne and Judith born in 1929, and Elizabeth born in 1934. Although legally she became Edith Bradbury, Edith continued to practise law under her maiden name. During the Second World War, while all three of her children were evacuated to Wales, Edith worked as an Enforcement Officer with the Ministry of Food.

On the 12th March 1946, Edith made Manchester headlines once again. Deputising for Judge F.R Batt, who had fallen ill the night before, Edith was the first woman to preside over the County Court. One newspaper seemed to communicate genuine surprise, with the heading, ‘Woman acts as Judge’, while another plainly stated, ‘Mrs Bradbury becomes Judge Edith for a day.’ According to the Express Newspaper, the Court Officials, ‘knew nothing of the change until they saw a tall, middle-aged woman in a black fur coat and felt hat step off the 8:40am Manchester-Macclesfield bus.’ Mr Dyer, clerk to the court “broke the news to the waiting counsel: ‘we’ve got a woman on the Bench today.’” The claimant is said to have made Edith smile by wrongly referring to her as ‘M’Lud’, while the ‘witnesses played for safety’ referring to her as ‘your Honour’.

After two hours work, Edith ‘lunched in the same room as four of the people over whom she had given judgement’ and ‘caught the bus to Manchester where she was due to give a law lecture at the college of Technology at 4pm.’ That evening, at her home in Whalley Range, Edith ‘had tea with her schoolmaster husband and children,’ a clear demonstration that apart from her achievements, she was an ordinary wife and mother.

Edith was actively involved in advancing women’s rights

On the 6th June 1951, Edith distinguished herself once more, this time alongside her 22 year old daughter, Anne, who, that evening was called to the Bar by Gray’s Inn. They were the first mother and daughter to be members together at the English Bar. In response to requests to interview Anne, Edith is reported as declaring ‘You may not speak to Anne. It would not be in keeping with the dignity of Gray’s Inn.’

In her spare time, Edith was actively involved in advancing women’s rights. She was the President of the Women’s Citizen Association in 1932, President of the Manchester Soroptimist Club in 1934, and vice-president of the Manchester branch of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom in 1936. Edith was also involved in various administrative tribunals, being awarded an OBE in 1951 for her position as Deputy Chairman of the Rubber Manufacturing (Great Britain) Wages Council.

Sadly, on June 19th, 1971 Edith died at her home in Manchester, aged 71.

Edith set many precedents in her career at the Bar and her story continues to inspire not only her family, but subsequent generations of women in the legal profession.

By Deborah Airey, 2nd Year Law Student at the University of Leicester

Janet Cohen, Baroness Cohen of Pimlico is a British lawyer and crime fiction writer. She sits in the House of Lords as a Labour peer.

Janet Hayes of Necton Consulting – Potential in People has recently completed some in-depth research into women’s journeys to partnership in professional services, interviewing lawyers as well as accountants and consultants. This was for an MSc in Coaching and Behavioural Change at Henley Business School.

Why is this important?

Women are still significantly under-represented at senior levels in organisations, despite decades-old equal opportunity and pay legislation and organisations’ focus on diversity. In large professional services firms, like PwC where Janet spent 18 years of her coaching and HR career, in 2017 fewer than 20% of partners were women. In the top ten UK law firms, the proportion of female full equity partners in 2018 was 19% (2013: 16%), although generally law firms recruit more women than men at trainee level.

In 2018, McKinsey’s researchers found that companies who were in the top 25% for the gender diversity of their executive team were 21% more likely to outperform on profitability. Inevitably, having fewer female leaders has a detrimental effect on organisations’ overall gender pay gaps.

Summary of findings

The women partners identified several closely interlinked influences from all stages of their careers that affected their choices in their transition to partnership. How these influences worked dynamically together was fundamental to the women’s identities. Their earlier experiences were key, their value being supported by cumulative advantage theory which maintains that a small advantage compounds over time into an ever-greater advantage.

Having early leadership responsibility seemed to play a key role in building individuals’ sense of self-efficacy, which in turn fostered adaptability and resilience. Neuroscience supports this finding by maintaining that early leadership responsibility prepares and inspires young adults to assume leadership roles.

How can women become leaders?

Seize early responsibility, supported by sponsors, mentors and coaches. Neuroscience tells us that early leadership responsibility prepares and inspires young adults to assume leadership roles. This small advantage over others then builds into an ever-greater advantage as women progress, building their sense of self-efficacy, which in turn fosters their adaptability and resilience, necessary to compete and lead in a volatile and uncertain world.

Raise profile: Raise profile: Women often believe that hard work is enough to get them promoted. It might be at the junior levels, but this changes. When those better at self-promotion advance ahead of them, women realise that they need to raise their profile and play the “political game” to be fairly rewarded for their achievements. Others can help with this: seeking out at least one sponsor is key to being represented at leadership level, and a coach can help women to publicise their achievements whilst remaining authentic.

How can organisations help?

– Give women the opportunity for early leadership responsibility. This will include encouragement and recognition from a wide range of other people, particularly sponsors, but also peers and their teams, as well as access to a coach at an early stage. Peer groups, both men and women, are especially appreciated for moral support with complex lives.

– Explicitly place more reliance on female values and definitions of success

– Use technology to support a flexible working culture where output is rewarded rather than input

– Identify and give more profile to female leaders to act as role models.

And outside of work?

Informal networks and those around women at home are invaluable, especially if the women have children. Of the women leaders with children that Janet interviewed, more than 50% have partners at home that are at least as involved in childcare as they are.

Student Emma Barker discusses how the First 100 Years campaign gave her the spark to write a fascinating A-level dissertation, diving into the social change and fearless campaigning that led to the passing of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919:

The First 100 Years campaign inspired me to research the history of women in the legal profession for my Extended Project Qualification (EPQ), the equivalent of half an A level. I discovered the First 100 Years campaign after a summer placement at a London Law Firm and subsequently won a school history competition when I used this knowledge to submit an essay on Helena Normanton, who was the first woman to be admitted into the Middle Temple. Although Normanton is not well known, her advocacy of equal pay, equal rights and female independence remain key issues today.

The lack of awareness about the first women in law as well as the upcoming centenary of the Sex Disqualification (removal) Act in December encouraged me to focus my EPQ on this topic. I spent a week studying primary resources in the archives of the Women’s Library at the London School of Economics. In order to gain an insight into views of the time, I read the Law Society Journal and Solicitors Journal at The Law Society Library. At ‘The Road to 1919’ symposium, at the Houses of Parliament, I discussed my EPQ with current researchers, including Judith Bourne a lecturer and leading author on Normanton. Following my research, I wrote a 5,000-word dissertation with the following dissertation title: To what extent was the admission of female lawyers into the UK law profession in 1919, under the Sex Disqualification (removal) Act, caused by the women’s suffrage movement?

My research explored the three main causes for the passing of the Sex Disqualification (removal) Act in December 1919. These causes were the women’s suffrage movement, the social and political context and the campaign by aspiring female lawyers, particularly the role of Helena Normanton and Ivy Williams.

At the end of my research I came to the conclusion that the women’s suffrage movement was not the lone cause for the passing of the Sex Disqualification (removal) Act in 1919. The suffrage movement was an important context for the Act as the suffrage movement demonstrated the need for equality. The passing of the Representation of the People Act in 1918 set the tone for the changes to come, arguably, anticipating the passing of the Sex Disqualification (removal) Act in 1919. Nevertheless, the persistent campaigning of aspiring female lawyers and certain male MPs helped to maintain the publicity for the cause within the press and Parliament. Although, the Emancipation Act was the final push towards the passing of the Sex Disqualification (removal) Act, I concluded that the sustained movement of aspiring female lawyers was a more significant cause as it helped accelerate the movement. Without the aspiring female lawyers’ desire to challenge public opinion and push open the legal profession to women the British Government would not have been pressured to pass the Sex Disqualification (removal) Act only a year after the Representation of the People Act.

by Emma Barker

Catherine Johnson is Group General Counsel at the London Stock Exchange. She advises the Board and senior executives on key legal matters and strategic initiatives, and previously was head of the Group’s Regulatory Strategy team. Catherine qualified as a lawyer at Herbert Smith in 1993.

Sabine is the Group General Counsel of BT, having worked all over the world, including in-house for two global beverage companies between 1993 – 2017.

Eleanor Sharpston QC has combined a career in practise at the Bar (specialising in European Union and ECHR Law) with an academic career first at UCL and then in Cambridge where she was a University Lecturer from 1992 to 1998 and an Affiliated Lecturer from 1998 to 2006. In January 2006 Eleanor took up the post of Advocate General at the European Court of Justice.

Rosemary is Group General Counsel and Company Secretary at Vodafone. She has been strongly involved in promoting innovation and diversity in the legal profession.

An exclusive interview with Rachel Spearing for First 100 Years. Spearing is a barrister at Serjeant’s Inn Chambers. Previously she worked in Capital Markets in a US investment bank. In 2017 Spearing founded the Wellness for Law UK Network, an organisation providing a space to share positive practice and initiatives to improve health and wellbeing at the Bar.

Elizabeth Johnson is the first female Chartered Legal Executive to be appointed a judge.

Elizabeth was appointed as a Fee-paid Judge of the First-tier Tribunal on 25 January 2019.

An exclusive interview with Dame Elizabeth Gloster for First 100 Years, sponsored by Simmons & Simmons. Gloster is a judge of the Court of Appeal in England and Wales, and was the first female judge of the Commercial Court.

Her Honour Eleri Rees is a Welsh judge. In 2012 she was appointed the Resident Judge of Cardiff Crown Court and Recorder of Cardiff, the first woman to hold this post.

Harriet Wistrich is an English solicitor who works at Birnberg Pierce & Partners. She is also the co-founder of Justice for Women, a feminist organisation which advocates for women who have fought back against violent male partners, as well as Liberty’s Human Rights Lawyer of the Year 2014.

Her Honour Judge Khatun Sapnara is a Circuit Judge who presides over both family and criminal cases. Her appointment in 2006 as a Recorder of the Crown Court saw her become the first person of Bangladeshi origin to join the ranks of the senior judiciary. HHJ Sapnara came to the UK from Bangladesh at the age of 6, going on to study at the LSE before being called to the bar in 1990.

Dame Nicola Davies was the first Welsh female Court of Appeal Judge when she was appointed in October 2018. In 1992, Nicola became the first female Welsh QC, having been called to the bar in 1976. Throughout her judicial career she has been the first Welsh woman to hold each post.

Baroness Patricia Scotland of Asthal PC QC, is a lawyer and Secretary General of the Commonwealth of Nations. Baroness Scotland was the first black woman appointed QC in 1991. In 2016, she became the first female Secretary General of the Commonwealth of Nations, a voluntary association of 53 members states with 2.4 billion people.

An exclusive interview with Hilary Heilbron QC discussing her mother, Dame Rose Heilbron, who was the first of two female QCs, the first female Recorder, and the first woman judge to sit at the Old Bailey.

These striking red robes, recently unearthed by the Royal Courts of Justice, provide a thread connecting decades of groundbreaking women in law, from the past to the present day.

The robes began their life in 1965 when Mrs Justice Elizabeth Lane reached the historic milestone of becoming the first woman High Court judge. This was only three years after she became the first woman County Court judge.

The bright scarlet robes were made specifically for her, thus starting out their life at a truly significant moment for gender equality in the legal world. The robes are the traditional dress of High Court judges presiding over criminal cases and earn those who wear them the nickname of ‘red judges’. For the first time, a woman would be known by that name.

Following Elizabeth Lane’s retirement in 1979, the robes were passed to Margaret Booth, appointed in that year as High Court Judge. She was just the third woman to hold that title by then, despite 14 years passing since Elizabeth Lane’s appointment, and was assigned to the Family Division. Mrs Justice Booth was also known for being the first woman Bencher at Middle Temple.

Margaret Booth made good use of her expertise in family law when she stepped into the role as head of the National Family and Parenting Institute following her retirement from the bench. There, she called for changes to divorce law, particularly in relation to custody settlements over children.

After Margaret Booth’s retirement, the robes soon found their way onto the shoulders of one Mrs Justice Hale, appointed judge in the Family Division of the High Court in 1994. This made her the first High Court Judge to have her prior career in academia.

She left the High Court in 1999 in order to become the second woman Court of Appeal Judge. Following this, her groundbreaking career has led her to become the first female Law Lord and, then, the first woman on the Supreme Court. She currently sits, of course, as the first woman President of the Supreme Court.

Following Lady Hale’s departure from the High Court bench, the robes were passed on to Mrs Justice Jill Black, appointed to the court in 1999. This followed a varied career at the bar across civil and criminal practise, with an eventual specialisation in family law. Lady Black then went on to sit at the Court of Appeal before becoming the second woman on the Supreme Court, where she joined a fellow wearer of the robes, Lady Hale.

Thus, when the Supreme Court in 2018 saw its historic first female majority panel, featuring Lady Hale, Lady Black and Lady Arden, two of the three women had been wearers of these same robes.

It is therefore fitting on this, the centenary year of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919, that the red robes worn by some of the most distinguished women trailblazers in the profession, from the first woman High Court judge to the first woman President of the Supreme Court, are to be presented in a display case for all to see at the Royal Courts of Justice. Do make sure you give them a visit.

Written by Ashley Van De Casteele, Project Coordinator for First 100 Years

At the heart of the legal profession is the concept of service and justice. This is encapsulated by the concept of pro bono in publico, “free for the public good,” a notion that does not exist in any other professional service.

This centuries old tradition of a lawyer acting in the interests of those without access to justice was first

institutionalised in commercial legal firms in 1997. I had the privilege of being appointed as the UK’s first full time pro bono solicitor by the partnership at Hogan Lovells (formally Lovells). The appointment was quickly replicated across the City with remarkable lawyers taking up roles as the City firms saw the need to address the access to justice gap.

For the most, the UK pro bono community is women-led, with some notable and inspirational exceptions – Paul Yates at Freshfields and Tom Dunn at Clifford Chance. The collective leadership of women in marshalling the talent and skills of their firms to secure access to justice is remarkable – and their passion to do more gives us hope in these fragile and fractured times.

– Yasmin Waljee OBE

Yasmin Waljee OBE

Senior Counsel and International Pro Bono Director, Hogan Lovells

Yasmin is an international human rights lawyer and was key to establishing a respected pro bono practice at Hogan Lovells. She founded the firm’s practice for victims of trafficking and forced labour and is currently acting for victims of sexual violence seeking accountability for ISIL foreign fighters. In her 22 years of practice as a pro bono lawyer she has succeeded in four UK policy changes including the introduction of a compensation scheme for British victims of terrorism abroad.

What will the next 100 years bring?

“Ideally groundbreaking leadership with firms willing to take on the greatest injustices which continue to exist and a challenge the rule of law: gender inequality across the Middle East; climate action to protect our fragile world; access to justice for those facing extreme income inequality; anti-corruption issues. And finally perhaps we will also see the appointment of the UK’s first Pro Bono Partner making pro bono a real legacy of St Yves.”

Felicity Kirk

International Pro Bono, Ropes and Gray

After 5 years in the Clifford Chance aircraft financing team in Paris and Tokyo, Felicity was asked to set up the Clifford Chance global CSR programme, and so began her 20 year career in pro bono. She moved to White & Case in 2000 to set up their programme outside the US, following this with a 2 year stint as London director of Lawyers Without Borders, a small NGO that leverages the power of pro bono to support rule of law programming in developing countries. In 2015, she joined Ropes and Gray to develop their London and Asia pro bono programme.

“It has been a huge privilege to have been involved in the growth and acceptance of pro bono in the UK, Europe and Asia. A particular highlights has been the collaboration between firms on a collective response to the Grenfell Tower fire supporting the North Kensington Law Centre

Shankari Chandran

Pro Bono Consultant, Ashurst

For a decade, Shankari Chandran was the Head of Pro Bono and Community Affairs at Allen & Overy. Appointed in 2000 to develop a global pro bono programme, she was based in London and her work spanned more than 30 offices around the world. Through the leadership of organisations such as the Law Centres Network and Reprieve, Shankari was part of coalitions that lobbied the UK government for better legal aid funding and advocated for the representation of detainees in Guantanamo Bay. She now works for Ashurst LLP, developing its law reform project which creates systemic change by improving laws that affect marginalised people.

“Whilst international law firms are still dominated by men at the partnership level, social change is largely driven by women. That’s not surprising – justice is a manifestation of respect, equality and empathy for our fellow human beings.’

Janet Legrand QC (Hon)

Former Senior Partner and Global Co-Chair of DLA Piper.

When she was appointed Queen’s Counsel Honoris Causa in 2018, the Lord Chancellor described her as a ‘pioneer in enhancing the role of women in the law, promoting social mobility, diversity and inclusion within her firm and the wider profession’.

As an Advisory Board member of New Perimeter, the firm’s global pro bono initiative, she has helped to guide the global practice’s strategic direction, supporting access to justice, social and economic development and sound legal institutions in under-served regions around the world. She has also leveraged her client relationships to develop long term projects on access to justice and economic empowerment in countries she has represented, such as Zambia and Timor-Leste.

“Pro bono is part of the glue that binds our firm together. In a perfect world, there would be no need for our pro bono practice, but as long as the need is there, I’m optimistic that our people will continue to volunteer and our practice will continue to grow in scale and impact.”

Elsha Butler

Head of Pro bono, Linklaters

Elsha has led Linklaters LLP’s pro bono practice for the past thirteen years; directing its strategy, internationalising it and taking it to scale. Recent successes include informing ASTI’s campaign for crucial changes to the law in the UK to tackle acid violence and securing successful claims for asylum in the UK by individuals fleeing persecution in their home countries due to being LGBT+. As well as her passion for social justice Elsha champions agile working, chairing her firm’s Family and Carers Network and supporting working parent initiatives.

“The strength of the pro bono sector owes a great deal to leadership by women. I’ve witnessed great evolution in the sector over time, and look forward to seeing the pace of evolution accelerate in the coming years as we capitalise on tech to innovate solutions to social challenges and injustice”.

Rebecca Greenhalgh

Senior Associate and Pro Bono Manager (USA and Asia)

Over the last 12 years she has managed a commercial law firm pro bono practice whilst also engaging and collaborating with the wider legal sector through a number of initiatives designed to increase pro bono impact. Rebecca was called to the Bar in 2007 and admitted as a solicitor in 2014.

Rebecca serves on the Secretariat for the UK Collaborative Plan for Pro Bono and she partnered with Felicity Kirk on behalf of more than 30 Plan member firms to co-ordinate the provision of pro bono support from across the legal profession to & through North Kensington Law Centre in the immediate aftermath of the Grenfell Tower fire.

Rebecca launched UKademy, a free annual professional development conference for law firm pro bono managers and now co-leads on the UKademy+ initiative, enabling pro bono professionals to share experience and insight throughout the year. Rebecca is the first non-US board member of the Association of Pro Bono Counsel (the global membership organisation for law firm pro bono professionals).

“Pro bono has allowed me to work with so many talented and inspiring women from all walks of the legal profession. I am incredibly fortunate to be part of a community where women are recognised and respected for their expertise and able to take on so many leadership roles. Although we are yet to see a UK firm create a pro bono partner role I know that day will arrive.”

Helen Rogers

Pro bono senior manager, Allen & Overy

Helen has led the pro bono programme at Allen & Overy since 2012. She also sits on the Pro Bono Committee of the Administrative Justice Council in the UK, and the Pro Bono Leadership Council of PILnet, the Global Network for Public Interest Law. Helen is Chair of Trustees of the Law Centres Network, the national voice of Law Centres and their clients, which strives for a just and equal society where everyone’s rights are valued and protected.

“To my mind, that is what all great female leaders have in common: humility, resilience and a commitment to creating opportunities for others. As the pro bono community continues to grow in the UK, we can draw inspiration from our clients and female colleagues across the legal profession to create a sector that is resilient and collaborative.”

Emma Rehal Wilde

Pro bono manager, Debevoise & Plimpton

Emma joined the pro bono profession in 2006, on the cusp of it becoming commonplace to see pro bono managers working in law firms across London. Emma was part of a small, women-only, team of pro bono heads that has set up the first exceptional case funding project for immigration detainees. She co-found a project that won the first ever state-funded compensation for a survivor of human trafficking. She also secured clarification on the legal position for women breastfeeding in public.

“Pro bono often provides opportunities for women lawyers to develop new skills and areas of practice. For women who feel like they can get lost in the crowd, pro bono gives them the chance to demonstrate their abilities and stand above their peers. In this way, pro bono has given women lawyers opportunities to shine and forge ahead with their careers as a result.”

The third woman judge and fifth woman QC in the country, through the eyes of her friend and fellow judge Her Honour Dawn Freedman

Perhaps the quality I most associate with Myrella is courage.

Having broken into the closed, to women, ranks of the Bar by starting her career at the Bar in her native Manchester, she followed her heart and, after marrying her beloved Mordaunt, moved to make a new start in Newcastle where he practised as a solicitor.

She didn’t need to try to emulate the men, as so many women who came after her felt they had to do. With her natural charm and formidable intellect she quickly rose to the top, all the while running her home and raising her two children within the true spirit of a “Jewish Woman of Worth”.

So respected was she by her fellows that her retirement party at Harrow was crowded with her friends and colleagues from Newcastle days, not least of whom were Lords Woolf and Taylor, at the time Master of the Rolls and Lord Chief Justice respectively, with the valedictory speech given by Lord Taylor.

As a mother, grandmother and model Judge, she was pre-eminently suited to hear the many cases arising from the Cleveland child abuse cases. Her judgements were legendary and, with their clear appraisal of the law and the facts, a privilege to read.

She gave up all the prestige she had earned, evidenced by her title as “the Queen of Newcastle” to again follow her heart to make yet another major move, this time, to London to be near her children and grandchildren.

However, it did not take long for her to become regarded as a great Judge and she was invited to sit at the Central Criminal Court. After trying it for a few sitting, she gave it up as she didn’t like the pomp and circumstance or being so far from her new home in Edgware.

Thereafter, until her retirement, I had the enormous pleasure of being her neighbour. She occupied Court and Room 5 and I Court and Room 6 at Harrow Crown Court.

She loved to joke that she and I were the only Judges who put the chicken soup (traditional Jewish Friday night fare) on the stove to cook before Court on Fridays.

It was sometimes difficult to associate the Judge who worked so assiduously to prepare her summings up, who ruled her Court with iron discipline but such charm, courtesy and kindness to witnesses and the Bar, with the grandmother whose living room was filled not with expensive pieces of art and antiques, but her young grandchildren and their toys.

It is a testament to her lack of ego that when she became Resident Judge following the retirement of HH Henry Palmer, she declined to move to the imposing Room 1, associated with the courtroom of the Resident Judge, Court 1.

Trying the most complex rape and child abuse cases, she was of course a natural with the victims, displaying empathy with them whilst always making sure defendants felt they had had a fair trial.

There was however a problem when the concept of video recorded interviews with child witnesses and evidence via CCTV came to Harrow. She refused to master its use, and her Usher who was of course devoted to her, was conscripted to do it for her.

Despite the burdens of the work and the administration involved in being Resident Judge, she found time to care for those who did not have her happy home life.

Together, we were Trustees of the Jewish Marriage Council.

Together, we drafted a prenuptial agreement for the Office of the Chief Rabbi to be signed by couples agreeing to behave in accordance with Jewish law if they divorced, which continues to be force, though technically not yet enforceable in English law.

Together, we played a role in drafting the Divorce (Religious Marriages) Act 2002 giving Judges the power to postpone Decrees Absolute until the parties had complied with their religious obligations.

In fact, after her retirement it could be said that Myrella found a second career as she could frequently be found in the corridors of the House of Lords hurriedly redrafting the Bill as it was debated in the House of Lords.

She was not just a great Judge and an inspiration to those who followed her, but she was a great human being.

By HH Dawn Freedman

About HH Dawn Freedman:

Her Honour Dawn Freedman began her legal career as a barrister before becoming the youngest person appointed as a stipendiary magistrate at the time, aged just 37. After this, she then became one of only a handful of female circuit judges and sat at Harrow Crown Court from its opening. There she developed a strong friendship with Judge Myrella Cohen QC.

Sandie Okoro is General Counsel at the World Bank. Sandie is named in The Powerlist 2019 as the fifth most influential and powerful black person in Britain.

Sylvia Denman CBE was a barrister and academic whose commitment to equal opportunities and fighting racial discrimination ensured a lasting legacy. She most notably conducted the Denman Inquiry into institutional racism in the CPS, heralding much-needed changes.

Sylvia was born in Barbados in 1932 and came to Britain to study law at the London School of Economics. She pursued a career as a barrister, being called to the Bar at Lincoln’s Inn in 1962. This was particularly impressive at a time when there were so few women and, in particular, so few black women at the Bar.

Sylvia began an academic career before joining the vanguard in the fight against discrimination in the 1960s and 1970s, serving as a member of both the Race Relations Board and Equal Opportunities Board. These were newly created bodies which enforced landmark legislation against racial and gender discrimination respectively.

Sylvia held multiple others positions over time. She was a member of the ethnic minorities advisory committee at the Judicial Studies Board, now the Judicial College. In this position, she played a key role in delivering the first race relations training programme in the country for circuit judges, from 1994 to 1996.

Meanwhile, the late 1990s formed a backdrop to increasing public awareness of institutional racism and a growing mistrust in the criminal justice system, mostly as a result of the Macpherson inquiry into the killing of Stephen Lawrence. Lawyers at the CPS began successfully challenging their employer before tribunals on grounds of race discrimination. Indeed, many black and minority ethnic employees at the organisation harboured a deep mistrust in their employer. All of this led to the director of public prosecutions asking Sylvia to lead an inquiry into race discrimination at the CPS.

The outcome, the Denman Report, was published in 2000. On all accounts, Sylvia conducted her inquiry with purposeful determination and without failing to consider equally the input of staff of all levels. As a testament to her uncompromising yet fair approach, the report’s strong criticisms and findings of institutional racism were firmly accepted by the director of public prosecutions.

The inquiry’s impact was major, with the CPS adopting a slew of policies aimed at implementing its recommendations. A key part of this was intensive diversity and equality training for all staff and greater accountability across the CPS for equality of treatment in the prosecution process. This helped start the process of making it a fairer place to work and rebuilding trust in the organisation, not least in the eyes of its employees.

To those that knew her, Sylvia was a person who did not suffer fools gladly but who always took the time to understand where people were coming from. Anny Tubbs, herself a lawyer and a former Chief Business Integrity Officer at Unilever, was both a personal friend of Sylvia’s and someone who looked up to her:

Sylvia was a family friend and the only lawyer I knew when I started down that route myself. She took me under her wing, nudging and nurturing me in equal measure. I used to joke that the reason I had many traineeship offers from law firms was because breakfast with her at the time had been more terrifying than any interview. She was very private about her work, but her sharp intellect and keen interest in others were apparent in all she did. She worked closely with equally engaged peers and leaves an important legacy for others to build on. She was a quiet yet determined trailblazer who deserves to be celebrated.

Even for those that didn’t know her personally, Sylvia will be remembered as a role model for channeling her deeply-held personal values into work that made huge strides in the battle against gender and racial discrimination in the UK.

Sylvia received a CBE for services to race relations and equal opportunities in 1994. She passed away in May 2019 at the age of 86.

Read Sylvia’s obituary

BBC’s Last Word, featuring Sylvia’s story

Greatest Career Achievements:

As one of only twenty listed in the Law category in The Sunday Times “Britain’s 500 Most Influential”, Penelope has not just led the way for CMS – she has led the way for the legal market. As the Law Society Gazette reported “Few women solicitors have smashed the “glass ceiling” into as many shards as Penelope Warne”.

Penelope trained and qualified as a solicitor with Slaughter & May where she spent five years. A move to Scotland saw her additionally qualify as a Scottish lawyer and turn her focus to the oil and gas industry. She initially set up her own firm and joined CMS in 1993, establishing the firm’s Aberdeen office and becoming the first female oil and gas lawyer in Scotland. Over the course of Penelope’s career, she has been instrumental in CMS’ global growth, spearheading the opening of new offices across Scotland, Middle East, Asia and Latin America. In 2013, she became The Senior Partner of CMS, one of the first female leaders of a global law firm.

She is an Honorary Fellow and Trustee of the Centre for Energy, Petroleum and Mineral Law and Policy at Dundee University. A member of the Foundation Board at IMD, the highly acclaimed international business school based in Lausanne Switzerland. She is also a member of the Board of the Law Society for England and Wales and a member of the Oxford University Vice Chancellor’s Circle.

Penelope has received many industry awards including The Lawyer’s Hot 100, “Senior Management Partner of the Year” at the British Legal Awards and most recently the UK Legal 500 Award for Outstanding Achievement. These awards are the product of extensive research and client recommendation. They are a testament to Penelope’s wider industry recognition for building a top quality oil and gas practice, a leading firm in Scotland, a new powerhouse firm in London and globally as well as her role as a great influencer of culture, diversity and women’s careers.

Highlights:

Penelope has had a successful and inspiring career – heading up the firm’s leading Energy practice and driving the firm’s international growth. Throughout her career, she has worked at the cutting edge of oil and gas issues; working with clients on ground-breaking transactions, pioneering on important thought leadership work across the sector including debating the future of energy with industry leaders at Davos, and partnering with governments, economists and leading universities across the globe.

Penelope’s vision to build a market-leading presence in Scotland resulted in her leading the successful merger with Scotland’s top firm Dundas & Wilson in 2013.

Three years later came a transformational moment for the UK legal market. Led by Penelope, CMS completed the largest merger in the history of the UK legal market, combining with Nabarro and Olswang to become the 6th largest firm in the UK and one of the top 6 globally. The merger was also transformational for the firm, providing significant scale to invest in technology and expand the global platform to become a progressive, modern, future-facing law firm – recognised in the last year as Law Firm of the Year by the British Legal Awards.

It has always been Penelope’s vision to build a successful dynamic firm, with a supportive culture where the careers of all can thrive. At CMS, she has developed and championed standout CSR and D&I initiatives which have truly influenced the world of law. Penelope has been instrumental in the firm implementing many policies and procedures to promote diversity including an enhanced maternity and shared parental leave programme as well as a new scheme “Time Out”, that allows employees to take up to four weeks’ unpaid leave each year.

What are some of the challenges for the future, challenges for women and the wider legal industry?

Looking ahead in a changing market, Penelope says law firms have to prioritise their culture, know their vision and purpose and remain agile and adapt. Further, it is important to embrace technology, not only in the way lawyers work, but also using it effectively in the way firms deliver services to clients. CMS was one of the first firms to move to a collaborative open plan office using technology.

On the challenges facing women in the legal profession, Penelope believes we must support gender diversity at all levels both junior and senior, have visible role models and follow through on policies. It is not just about advancing women in senior roles; it is important to foster millennials through developing a flexible mindset and supportive culture which embraces mentoring and agile working and eliminates unconscious bias.

She adds: “We must work together in the legal industry to tackle this issue. As a proud advocate of women in business, and with 30% women on our board and in our partnership, we regularly work with clients and other organisations, schools and universities to share experiences of best practice. In this way, we can help change perspectives in our communities and throughout society. Our clients value the work we do and it gives us a very different relationship with them. We have worked together with many clients on their D&I strategy, with a special focus on LGBT, Gender and Ethnicity. We benefit from their programmes and we share ours with them.”

Finally, Penelope emphasises that her enthusiasm for a challenge, her inspiration and zest for life is boosted by three very special people: Anthony to whom she has been married for 30 years and her two children William and Sarah.

Jessie Chrystal Macmillan was a Scottish feminist, barrister and politician. She was the first female science graduate from the University of Edinburgh, the first woman to plead a case before the House of Lords and a founder of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

Born in 1872, Chrystal grew up in Edinburgh alongside her eight brothers. Their father was a tea merchant. After attending boarding school in St Andrews she enrolled at Edinburgh University in October 1892, becoming one of the first female students in Scotland. When Chrystal graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in April 1896 she was the first woman at Edinburgh to do so.

After spending some time studying in Berlin, she returned to Edinburgh University, studying in the Faculty of Arts and graduating with an MA in April 1900. She was the first woman to graduate with first class honours in mathematics and natural philosophy in April 1900, and also earned second-class honours in moral philosophy and logic.

At university, Chrystal became involved in student politics, chairing the Women’s Representative Committee and lobbying the Scottish University authorities on gender parity for scholarships. She was also Vice President of the Women’s Debating Society and active in the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Aside from politics, she was the second woman member of the Edinburgh Mathematical Society.

Chrystal was the first woman to plead a case before the House of Lords in 1908. As a graduate, she was a member of the General Council of Edinburgh University but was unable to vote for the MP who would represent the university’s seat in 1906. Chrystal argued that the use of the word “persons” in the General Council’s voting statues did not exclude women as female graduates are persons. The case was lost before the University Courts but Scottish suffragists raised £1000 for the case to be heard in the House of Lords.

When Chrystal arrived at the House of Lords, arrangements to prevent women from entering had to be suspended (they had been instigated due to the activities of militant suffragettes). She spoke for three-quarters of an hour and was portrayed very positively in the press as a “modern Portia” with an “admirable speaking voice” and “complete self-possession”. The case was rejected, but the press was highly supportive of the plight of these educated women and it generated worldwide publicity for the suffragist cause.

In the suffragist newspaper The Vote, Chrystal wrote in 1909:

I want the vote for women because they are different from men, different in the external accident of life and in much of the work they have to do. To be just, a Government should represent such differences. And I want the vote for women because they are the same as men, the same in those fundamental human qualities in virtue of which a share in self-government is given to men. Both are moral beings.

Chrystal moved to London and 1911 she attended the sixth congress of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance (IWSA) in Stockholm. Collaborating with European women to document women’s voting rights around the world, they produced a book,Woman Suffrage in Practice, in 1913. Chrystal acted as the IWSA vice-president from 1913 to 1923.

During the First World War, British suffragists were divided between patriots and pacifists. Chrystal was a pacifist campaigner, spending time providing food for refugees and working to find peaceful resolutions to the war. Chrystal helped to organise the International Congress of Women in The Hague in 1915, which consisted of 1,150 women from North America and Europe discussing how to halt the war. Although 180 British women planned to attend the Congress, many were left unable to travel after Winston Churchill cancelled British ferry services. However, Chrystal attended the conference along with two other British women and was selected as a committee member. She championed the Congress’ proposals to heads of neutral states including President Woodrow Wilson, and some of their proposals were incorporated into Wilson’s Fourteen Points.

Chrystal was a delegate at the International Congress of Women in Zurich, which criticised the Treaty of Versailles. Along with other feminists, she took their resolutions to the 1919 Paris Peace Conference and advocated for the establishment of the League of Nations. Chrystal unsuccessfully lobbied for the separation of women’s nationality from their husband’s, and the women were mostly ignored at the Conference. The UN eventually changed the law on nationality in 1957, in part thanks to Chrystal’s tireless campaigning.

Following the passing of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919, Chrystal applied to become a student of Middle Temple, believing that becoming a lawyer would be the most effective way to continue to campaign. Alongside her studies, she co-founded the Open Door Council which campaigned to repeal the legal restrictions on women and give women equal opportunity in the workplace.

Called to the Bar in 1924, she joined the Western Circuit in 1926 and became the second woman to be elected to its Bar Mess. She acted as counsel for the defence in six cases on the Western Circuit and continued to practise in the North London Session courts until 1936. From 1929 she also appeared at the Central Criminal Court in five cases for the prosecution and one for the defence.

Chrystal’s friend, the writer Cicely Hamilton wrote that she was:

The right kind of lawyer, one who held that Law should be synonymous with Justice … Her chief aim in life – one might call it her passion – was to give every woman of every class and nation the essential protection of justice. She was, herself, a great and very just human being … She could not budge an inch on matters of principle but she never lost her temper and never bore a grudge in defeat.

In 1929 Chrystal co-founded the Open Door International for the Economic Emancipation of the Woman Worker and remained president until her death. She also worked to end sex trafficking and campaigned for the civil rights of prostitutes, opposing state regulation of prostitution.

In 1935, she stood for election as a Liberal in Edinburgh North but received less than 6% of the votes. In May 1937, she wrote an article for the International Woman Suffrage News on the necessity of being impatient with regards to women’s rights. “Women like to think of men as their equals not their inferiors, so in this case the exercise of patience is not called for when men are behaving badly, disregarding justice and exhibiting a very unfounded sense of superiority”, she wrote.

In September 1937, Chrystal died of heart disease. In her obituary in The Scotsman, Chrystal is remembered:

Miss Macmillan directed her whole energies to the important questions of securing women’s statutory, social, and economic equality with men… she demanded one law for men and women and fought out-of-date legislation and proposals. Women will never know how much they owe to her dogged persistence in fighting their cause.

A building at Edinburgh University is named after Chrystal, and the Middle Temple continues to award a Chrystal Macmillan Prize to an outstanding female law student.

Written by Annabel Twose, Project Coordinator of First 100 Years

In 1987, Anne Willmott, a trained counsellor, was recruited by a forward-thinking Chief Fire Officer to set up a professional Counselling and Advice service for the London Fire Brigade. In a conversation with First 100 Years, she discusses the obstacles she came up against, working in a male-dominated environment, and what needs to change in our work culture.

Teamwork was the foundation of the macho culture in the 1980s, and firefighters had to show tough exteriors at all times, believing that to show feelings of any kind would imply weakness. They knew that, regardless of problems at home or at work, they had to be seen to be strong.

Anne says she soon became aware of the high levels of sickness absence and was determined that the new service, which aimed “to keep people at work in times of difficulty” could make a cost-effective contribution to overall efficiency.

As Anne began the slow process of developing relationships, building bridges and earning trust, it was important to acknowledge the many expressions of hostility and wariness; she was told “we managed all these years without someone like you.” True. Anne believes that respecting the tradition of firefighters coping in their own way, was vital. Gradually though, she was able to help groups and individuals, recognise that there could be a price to pay later for “managing” so well. Suppressed feelings – rage, sadness, loss, helplessness – can result in unrecognised depression, relationship problems at home and work, as well as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) which at that time was almost unheard of.

A few months after the service was set up, the King’s Cross Underground Fire killed 31 people, including a Senior Fire Officer. Whilst being a hugely traumatic event for the Fire Service, Anne says it provided an opportunity for the first time, to meet every firefighter involved to talk through the incident with the aim of preventing the onset of PTSD. Following this major disaster, she then set up a protocol for debriefing after all serious incidents, in order to process feelings at the time rather than burying them and possibly causing later problems.

Anne remembers when women first joined the Fire Service. There was enormous resistance and suspicion from may in the male workforce. Female firefighters had to struggle to prove themselves and be accepted. But the Fire Service management put great emphasis on Equality Policies and this played a key part in the profound and lasting culture change which followed.

Over time, the presence of female firefighters has had a huge and positive impact on the workforce and its public perception and image. They have provided role models for young women from a wide variety of backgrounds and The London Fire Service now proudly has its first female Commissioner, Dany Cotton.

In many areas, such as finance and law challenges remain, with ongoing debate about how to make these male-dominated environments more welcoming to women. In some areas of the legal profession, work culture still needs to change in order to improve mental and physical well-being, as well as diversity.

Anne herself remembers her fifteen years in engineering and how she was gradually side-lined and given less prestigious work following the birth of her daughter. She believes the Fire Service has shown what can be achieved when an organisation commits itself to positive change.

Interviewed by Annabel Twose, Project Coordinator of First 100 Years

Averil Katherine Statter Deverell was one of the first women, along with Frances Kyle, to be admitted to the bar in Ireland on November 1st 1921. It was almost a year later before Ivy Williams became the first woman to be called to the English Bar.

Little is known about Deverell’s life. Born in Dublin on the 2nd January 1893, her parents were William Deverell and Ada Catherine Slatter Deverell. She had a twin brother, William Berenger Statter Deverell. She attended the French School, Bray, Co. Wicklow from 1905 to 1909, and appeared in many of their dramatic productions. She continued to act when she attended Trinity College and was involved in the Dublin University Dramatic Society. Her scrapbook from this time includes a programme from a suffragette play. Averil was presented at Court to King George V and Queen Mary on the 8th July 1911.

Deverell was among the first female graduates from Trinity College, Dublin, and was awarded a law degree in 1915. She served as an ambulance driver in France and Flanders in 1918. In January 1920, she became a student at King’s Inns along with Frances Kyle, following the passing of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act. Averil was called to the Bar on the same day as her brother, William.

Two years after this, Mary Dorothea Heron became the first woman admitted as a solicitor in Ireland, although she never took out a practising certificate.

In 1928, The Londonderry Sentinel reported that Averil became the first Irish woman barrister to appear before the Privy Council in London. She was also the first woman to appear in the Supreme Court of Ireland and the Court of Criminal Appeal in Ireland. Alongside her work at the bar, she was a keen breeder of cairn terriers, naming her home “The Brehon Kennel”.

Averil remained in practice until she retired in 1969. She died on the 11th February 1979, aged 86. A portrait of her hangs in the Law Library of Ireland, and a lectureship in the Law School of Trinity College is named after her.

Photographs © British Newspaper Archive

Read More

Liz Goldthorpe – From Presentation to Pioneer – Averil Deverell and Dublin Castle

King’s Inn Library, ‘The Averil Deverell Exhibition’, 23 April 2018

J. Harford & C. Rush, Have Women Made a Difference? Women in Irish Universities, 1950 – 2010 , Peter Lang Publishers, 2010

‘Lady of the Law’, Dublin Evening Telegraph , 29 January 1920, p.2

‘Ladies Apply for Admission as Law Students’, Dublin Evening Telegraph , 22 January 1920, p.2

‘Belfast’s Woman Barrister at Work’, The Vote , 3 March 1922, p.70

‘Ireland’s Great Dog Show’, Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News , 31 March 1954 p.312-313

‘The Law’s Delay Prevents Coloured Woman Barrister’s Appearance’ Northern Whig , 25 July, 1928, p.12

‘University Intelligence, Trinity College Dublin’, The Belfast News-Letter, 8 November, 1911, p.2

‘Lady Law Students’, Weekly Freeman’s Journal , 24 January 1920, p.5

‘University Intelligence, Trinity College Dublin’, Dublin Daily Express – 09 May 1911

‘Transferred Civil Servants. Free State Claim Before Privy Council’, Londonderry Sentinel, 26 July 1928, p.8

Frances Kyle was one of the first women, along with Averil Deverell, to be admitted to the bar in Ireland on November 1st, 1921. They were among the first women to be called to the bar anywhere in the world. It was almost a year later before Ivy Williams became the first woman to be called to the English Bar.

Little is known about Frances’ life. Born on the 30th October 1893 to Kathleen Frances Bates and Robert Alexander Kyle, her parents had married in New York, before moving back to Belfast. Her father was the son of Mr G. W. Kyle who had founded G.W. Kyle, drapers, outfitters, &c., which was a well-known business in Belfast. Robert inherited the business upon his father’s death. He was also an enthusiastic yachtsman, a member of the Belfast Natural History and Philosophical Society, and a microscopist with “the finest collection of microscopes in Ulster”, according to his obituary in The Northern Whig and Belfast Post. Robert is described as “a man of benevolent disposition, and all philanthropic and social welfare work found in him a generous supporter.” Frances had a sister, Kathleen, who married a medical inspector, Dr. John McCloy. In 1930 Kathleen was described by the Belfast Newsletter as “very well known in Belfast” and “a delightful speaker”.

Frances received a BA in French from Trinity College Dublin in 1914, and an LLB in 1916. In January 1920, Frances and Averil were admitted as the first female students of law at King’s Inns, Dublin. Frances came first in the Bar Entrance Examinations and was the first woman to win the John Brooke Scholarship. The Irish Times described this as “a women’s invasion of the law.”

When Frances and Averil were called to the Bar on the 1st November 1921, they were part of the first cohort of people to be called since the Irish Judiciary became independent from England. Averil became the first woman to practise at the bar anywhere in the world. Two years after this, Mary Dorothea Heron became the first woman admitted as a solicitor in Ireland, although she never took out a practising certificate.

In 1922, Frances was elected a member of the circuit of Northern Ireland at a meeting in Belfast, becoming the first female member of a circuit. Frances is reported in the Dublin Evening Telegraph in 1922 as having received eight briefs. She told a Daily Mail representative:

“I’m not at all certain that the first women barristers will succeed in making a living at the Bar. Legal friends advised me to devote myself to conveyancing, which does not require attendance at the courts, but I felt that the first woman barrister should practise, if possible, to prepare the way for those who will follow.”

Frances’ mother died in 1930 aged 63, and her father died in 1931 aged 82. Frances seemed to have struggled to find work, and her last listing in Thoms Law Directory is in 1931. In 1937, she appeared in court to defend herself on a parking summons. By 1952, Frances was living in London with her sister Kathleen. She died on the 12th February 1958, aged 64.

Written by Annabel Twose, Project Coordinator of First 100 Years

Georgina “Georgie” Frost was the first woman to hold public office in the UK and Ireland.

Born on the 29th December 1879 in Sixmilebridge, County Clare, Georgie was one of five children. Her father was the petty sessions clerk of Sixmilebridge and Newmarket-on-Fergus. Before that, Georgie’s grandfather John Kett had also acted as petty sessions clerk, so the job was something of a family tradition.

Between 1909 and 1915, Georgie helped her father in his duties and sometimes performed them herself, becoming well-known in the area during this process. When Thomas Frost retired, the local magistrates elected Georgie to succeed him. However, at this time all appointments had to be approved by the Lord Lieutenant who rejected the appointment, arguing “a woman by virtue of her sex is disqualified from being appointed or acting as Clerk of Petty Sessions.”

Undeterred by this, the magistrates granted Georgie a temporary year-long contract, in order to give her time to fight her case. However, she was again rejected by the Lord Lieutenant. Represented by Tim Healy KC and James Comyn KC, Georgie brought the case to the chancery division in Dublin under the ‘petition of right’ procedure. However, in echoes of the infamous Bebb v The Law Society case, Mr Justice Dunbar Barton dismissed her claim saying that it was a matter for parliament, referring to the Statutes governing the Office of Clerk of Petty Sessions, and arguing that there had never been a woman Clerk of Petty Sessions.

He commented:

The reason of the modern decisions disqualifying women from public offices has not been inferiority of intellect or discretion, which few people would now have the hardihood to allege. It has been rather rested upon considerations of decorum, and upon the unfitness of certain painful and exacting duties in relation to the finer qualities of women.

Georgie did not give up, taking her claim to the court of appeal in November 1917, before Lord Shandon, Lord Chief Justice Molony and Lord Justice Stephen Ronan. By the time judgement was delivered in December 1918, Lord Shandon had resigned, although he left a letter instructing that the appeal should be granted because no statues or principles of common law disallowed a woman being appointed. Despite this, the other judges upheld the decision that Georgie was excluded from public office, arguing that it was a rule of common law women could not be appointed to public office.

Georgie brought the case to the House of Lords in forma pauperis because there had been a dissent in the Irish court of appeal. This meant that if she was unsuccessful she would not be required to pay the costs. By the time the case was listed for hearing on the 27th April 1920, the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 had passed, which removed any legal bars to women being appointed public office. Retrospective approval was therefore granted to Georgie, who was appointed in April 1920, making her the first woman to hold public office in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland after a lengthy fight which had spanned several years.

During the Irish Civil War, Georgie retained the position and was held at gunpoint by the IRA, and the petty sessions court house from which she worked was destroyed. However, her career proved to be short-lived, when in 1923 the Irish Free State abolished her job.

Georgie died on the 6th December 1939, aged just 59.

Written by Annabel Twose, Project Coordinator of First 100 Years

Margaret Owen OBE is a human rights barrister specialising in women’s rights. In an interview with First 100 Years, she discusses her varied career, founding the charity Widows for Peace Through Democracy, and her advice for young female lawyers today.

Margaret was born in 1932, the daughter of a solicitor and a doctor. She remembers her father as “a very good solicitor. We didn’t talk about human rights in those days, but that’s really what he was doing.” Her family on her mother’s side had come to England to escape pogroms in Lithuania. Despite her disadvantaged background, Margaret’s mother secured a scholarship to Cambridge and later became a doctor. She also helped to set up the National Marriage Guidance Council.

Margaret grew up in London but was evacuated during the war to the countryside, after a near miss with a German U-boat. “We were all about to go to America, but my elder brother said to his headmaster ‘Sir, I can’t leave my country when it’s at war’, so my mother cancelled the ship we were to go on. The ship was torpedoed, so the only reason I’m here now is because we didn’t get on that ship.”

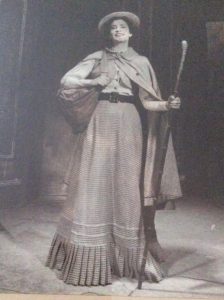

Initially, Margaret wanted to become an actress. “I acted a great deal at school, but when I got to Cambridge I read law, because I saw myself as a sort of Portia, dispensing justice and the quality of mercy. I went up to Girton College in 1950, and there were only two women in the whole year reading Law at the time. There were no women law dons so all our supervisions were at other colleges.” Whilst at Cambridge, she continued to act alongside directors Peter Hall and John Barton, as well as Dadie (George) Rylands, the King’s Fellow and Shakespeare scholar, playing parts including Gertrude in Hamlet and Goneril in King Lear. “Maybe there’s something about advocacy and theatre which go together.”

After leaving Cambridge, she studied for the Bar, and completed her pupillage at 4 Paper Buildings in 1954, in the same chambers as Quintin Hogg, who received briefs from Margaret’s father. Her pupilmaster was Maurice Drake, who went on to become a High Court Judge. Margaret describes the atmosphere in chambers as “extremely difficult” for female barristers. “There were boys in the chambers who were going to get all the best work”, she recalls. “They were probably in their early forties, because the war meant that a lot of men had gone into the army, the navy and the air force. Then they came back, and they were already quite a lot older than us, so that made it extremely difficult for us to get briefs.”

Disillusioned, Margaret left the Bar for a time and got a job at the advertising agency J Walter Thompson when commercial television was in its infancy. “Lots of my friends were in advertising and everything seemed quite exciting, and I completely forgot I was a lawyer”, she recalls. In 1956 she moved to Granada Television, working on documentaries.

After marrying, Margaret started a degree in anthropology at Manchester under Max Gluckman. “I was always interested in how law impacted people, and how people, particularly the most vulnerable, could have a role in actually developing the law, implementing the law or monitoring its effects”, she explains. However, when her husband got a Chair at Imperial College they moved back to London and she completed a diploma in social administration at LSE in 1968, getting the only distinction of the year. Alongside her studies, she was also looking after their four children aged 1, 3, 5 and 7.

After she graduated, Margaret sat on a committee for the coordination of the welfare of Ugandan Asians after Idi Amin ordered their expulsion, and she travelled to India to write a report called ‘Stranded in India’ about the Ugandan Asians who were stranded in India. Later, she became senior counsel for the UK Immigrants Advisory Service as an immigration and asylum lawyer, travelling around the world and working on a diversity of cases, including Vietnam War draft avoiders in the US and Bangladeshi family reunion cases. When she left UKIAS, Margaret became head of law and policy at the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), the umbrella organisation for all the family planning associations. This involved travelling around the world to work on women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights, and the status of women generally.

In 1990, Margaret’s husband died. At the time she was teaching judicial administration to commonwealth magistrates and a Malawian magistrate asked Margaret to help a sick baby from Malawi. Margaret invited the baby and its mother to stay with her whilst the baby received treatment. Arriving at Margaret’s house, the mother said to her “You mean your husband’s brothers let you stay here and keep all these things?” This question prompted Margaret to research widow’s rights, and she discovered that there was no international organisation for widows.

Margaret went on to found Widows for Peace Through Democracy, a charity with ECOSOC status which campaigns for the rights of widows. “I was conscious of how many women are bereaved because of conflict, and how many women are wives of the missing or the disappeared. We need to have widows’ voices at peace accords.” While there have been improvements, she is concerned about the gap between the laws countries pass, and their implementation on the ground. “There’s a huge gap between the cup and the lip, these laws are not implemented, particularly in rural areas.”

In 2000, the UN passed Security Council Resolution 1325 which calls for a consideration of the needs of women and girls during conflict and requires parties in a conflict to prevent violations of women’s rights and to support women’s participation in peace negotiations. In response, Margaret helped to set up Gender Action for Peace and Security UK (GAPS-UK), which promotes and facilitates the meaningful inclusion of gender in the UK’s peace and security policies.

Margaret is also a Patron of Peace in Kurdistan and is passionate about promoting the rights of the Kurdish people who are one of the largest stateless groups in the world. She has visited the autonomous region of the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria (DFNS), known for its gender equality and democratic socialism, and she believes we can learn a lot from them. “There’s an incredible society there, every institutional organisation must have male and female co-chairs, even the army. They’ve done so much to reduce violence against women, it’s an incredible model.” She is also very concerned with the political situation in Turkey. Currently, over 70,000 university students are imprisoned in Turkey, and more professional journalists are detained there than any other country in the world. Margaret and regularly travels there to monitor trials and elections.

Margaret thinks to be a successful lawyer, you have to have “a passion for the truth, and a clarity of vision”, as well as powers of concentration. Does she think that the working environment has improved for female lawyers today? “In some ways it’s got better for women in law, but in other ways it is not. We may have more women in the Supreme Court now but compared to other countries we still have a low percentage of women in the judiciary. The UK also has the highest childcare costs in the whole of Europe, so it’s still difficult in terms of career gaps to get to the highest pinnacles of the profession along with men.” She’s also concerned about social mobility. “My grandchildren are paying a bomb to go to university, and so many internships are in London. How can people from disadvantaged families afford to do them?”

Her advice to young female lawyers is:

Just keep at it, and if you see any sort of prejudice or obstacle or unfairness in the way you are being treated, recruited or promoted, make a fuss. Speak out. Don’t let these things happen anymore. Don’t join the boy’s network, if you’re going to have a network make sure it’s really comprehensive and covers everybody irrespective or religion, ethnicity or class. Look after the other women around you, the women below you, and be sure you bring other women up with you.

Margaret is now a Door Tenant of 9 Bedford Row and she regularly writes for their international law blog. Aged 86, she is still passionate about speaking up about injustices, both at home and abroad. “I’m very glad to be a lawyer”, she says, “it is with my legal hat on that I feel I can wield some authority.”

Written by Annabel Twose, Project Coordinator of First 100 Years

The ‘rebel Countess’ Constance Markievicz née Gore-Booth was an Irish revolutionary, founding member of the Irish Citizen Army, suffragette and the first woman elected to the British House of Commons on the 28th December 1918, although she did not take her seat. She was also one of the first women in the world to hold a cabinet position as Minister for Labour of the first Dáil Éireann (Irish Parliament) in 1919. Ireland had to wait until 1979 for its second female cabinet minister.

Born in 1868 in London, Constance was the eldest daughter of Lady Georgina Gore-Booth and Sir Henry Gore-Booth, an Anglo-Irish landlord and Arctic explorer. The family lived at Lissadell estate in Co. Sligo, Ireland. She had a privileged childhood, educated by a governess and enjoying hunting and riding. In 1887, she was presented at court to Queen Victoria in her Jubilee year. However, the famine of 1879-1880 greatly coloured Constance’s views and left her with a great concern for the welfare of the poor. Her father provided free food for his tenants at Lissadell House, which inspired Constance and her sister, Eva. She also became interested in women’s suffrage as a young woman, presiding over a meeting of the Sligo Women’s Suffrage Society in 1896.

Constance trained as a painter at Slade School of Art in London, before continuing her studies in Paris at the Academie Julian. There, she met her future husband Casimir Markievicz, an artist from a wealthy Polish family. He was known as ‘Count Markievicz’, although there was some question over the validity of his title.

Constance and Casimir married in 1900, and in 1901 she gave birth to a daughter, Maeve, who was raised by the Gore-Booth grandparents at Lissadell. In 1903, Constance and Casimir moved to Dublin and began participating in its artistic scene which was going through something of a renaissance. They helped to found the United Arts Club in 1905. Although ostensibly apolitical, the club included many Irish nationalists including Douglas Hyde, who would go on to become the first President of Ireland.

Through their artistic connections, Constance met revolutionaries including Maud Gonne, and her politics underwent gradual radicalisation. By 1908, she was active in nationalist politics and had joined Sinn Féin and Inghinidhe na hÉireann (‘Daughters of Ireland’), a revolutionary women’s movement founded by Maud Gonne. She also helped to found Bean na hÉireann (‘Women of Ireland’), Ireland’s first women’s nationalist journal. Constance and Maud also performed several plays at the Abbey Theatre, which highlights the relationship between Dublin’s flourishing cultural scene and burgeoning Irish nationalism.

In 1909, Constance co-founded Fianna Éireann (‘The Fianna of Ireland’), an Irish nationalist paramilitary youth organisation which trained teenage boys to use firearms, in preparation for a war of Irish independence. At its first meeting, she was almost expelled from the organisation for being a woman, but her co-founder Bulmer Hobson ensured she remained and she was elected to the committee.

In 1911, Constance was arrested for the first time for speaking at an Irish Republican Brotherhood demonstration which was protesting George V’s visit to Ireland. She handed out leaflets, threw stones at pictures on the King and Queen and attempted to burn the British flag. This only spurred her on, and she joined the socialist Irish Citizen Army (ICA), a volunteer force aimed at defending demonstrating workers from the police. She also designed their uniform and composed their anthem.

During the Dublin lock-out of 1913, an industrial dispute involving over 20,000 workers, Constance sold her jewellery in order to help pay for food to be distributed to the workers’ families. She also ran a soup kitchen for poor children. By this time, Casimir had moved back to Ukraine to become a war correspondent in the Balkans, although the separation was amicable and they continued to correspond.